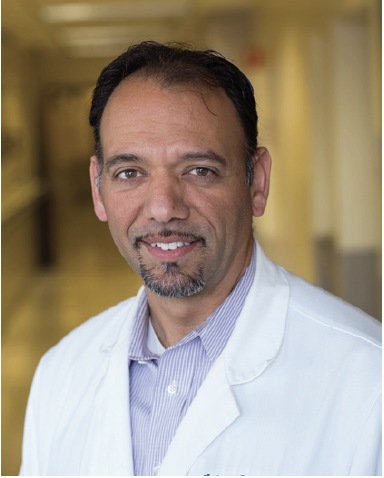

Faculty Interview: Antonio Gomez, MD

A Conversation with Antonio Gomez, Associate Professor in the Division of Pulmonary at ZSFG

Where were you born and raised? Tell me about your family.

I was born in Long Beach, CA. My parents were both born in Cuba, but met in Orange County. My sister is a social worker in Los Angeles with the school district and I am very proud of her because she went on strike a few months ago with the teachers for better conditions.

My dad is the youngest of fourteen kids and was born in Santiago, Cuba, near what we know as Guantanamo. He grew up working on the family farm not sure of what the future would bring. Eventually, he was called to the ministry inspired by what can only be described as a vision he had in his early 20’s — Episcopalian priest because he wanted to have a family. He went to seminary, was ordained as an Episcopalian priest, and had his congregation in Havana. In the late 60s, he realized that the Communist regime was attempting to purge Cuba of religious institutions and everything he’d worked for. So, he began the long process of obtaining permission to leave the island which obligated him to work in the fields manually cutting sugarcane for 18 months. He then went to Spain during the Fascist regime of Franco for seven months as he was cultivating roots in Southern California, via family and the Episcopalian church, where he met my mom fairly soon afterwards. She and her sister were part of the Peter Pan Migration, mostly kids who were sent here without parents as part of an effort between the Catholic Church and Pan American Airlines; this wave lasted for around 18-24 months, during which the Cuban government didn’t challenge it. My aunt and mom didn’t have family living here so they were sent to an orphanage in Arizona where they stayed for a couple of years. They and my grandparents were finally reunited six years later. Ironically, my mom and dad’s families both settled in the same southern California area and, as Cuban families do, matched my parents up. They married in 1972, and I arrived nine months later.

Describe your fondest memories and adventures growing up.

I was inquisitive and didn’t mind exploring and doing things outside of my comfort zone. Sports were a huge part of my life: I played Little League, swam, rode my bike all over the neighborhood, played water polo in high school, and traveled all over Southern California to play tournaments. We did a lot of car camping as a family because we couldn’t afford “real” vacations and would camp a couple of weeks at a time in Colorado, Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming and Montana, and Olympic National Park on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington. In college, I backpacked through much of South America and to Costa Rica, where I roomed with a family in Monte Verde cloud forest and worked with some botanists studying seed dispersal in the cloud forest; I worked for them for about a month. I already knew that I was going into Medicine and realized that time was important because once I began medical studies, I would not have such an opportunity again for a long time. At the end of med school, some friends and I took a round-the-world trip that was so worthwhile. This happened a few months after 9/11 and we visited Bangkok, Nepal, Kenya and Egypt, and were treated with kindness and respect.

Have you ever surprised yourself by a non-medical achievement? What was the prize or reward?

When I was 16, I was the first team all-tournament goalie on our water polo team when we won the Junior Nationals in Clovis, near Turlock, so I was happy about that. The other achievement was playing water polo all five years at Cal, which was highly competitive, and maintained my GPA so that I could reach my goal of applying to medical school.

If you could prepare dinner for your great-grandparents, what would be on the table? And, what would you want to know of their lives?

I am told that my mom’s grandmother was a great cook and taught my mom almost everything she knows about preparing a meal. My mom then passed that love of cooking and sharing a meal with family to me. By contrast, my mom’s mother was a terrible cook who hated the kitchen and yet made the best flan ever! I would hesitate to make a Cuban dish, but the act of cooking is an act of love and, in a Cuban home, a meal is a social event when we spend hours at the table with wine and conversation. The best dishes are those that take time so I would probably braise meat, like a brisket, in a dutch oven over several hours. I would ask my great-grandmother about her family, half of which was Spanish and the other side was French. I’d want to know what brought them to Cuba - be it war, famine, faith – and was it worth it?

Why did you become a doctor? How did you choose Pulmonary as your field?

I was always interested in science and math, and I had three components to my foundation and how I approached Medicine. My grandfather was an engineer in the Cuban navy, and he and his older brother taught me chess, which offers scientific, mathematical solutions to a problem. It helped me understand the build-and-construct mindset in understanding systems. My dad, because of his focus on social justice through his faith, influenced how I approach patients. My mom, who was more of an educator, is part of my foundation as a teacher. I went to UC Davis for med school thinking I was destined for primary care. There, I was heavily influenced by a master diagnostician, Dr. Faith Fitzgerald. I realized early on that I would never reach her heights as a diagnostician – she is incredible – but she also showed me what it was to be an outstanding medical educator. I chose pulmonary and critical care medicine because I really enjoyed the weird, very extreme physiology affecting multiple organ systems that occurs in the ICU – much of which often center on the seemingly simple act of air moving in and out of the lungs.

Could you speak to culture change within the Latino community towards more visibility in the professions of healthcare?

My history within the UC system goes back to 1991 so my perspective might be slightly different than some. I think the university has come a long way in the past 20 years with regard to increasing diversity in medicine, but it has been slower than I would have anticipated when I started medical school in 1998. In addition, even though the number of faculty and staff who are from underrepresented groups has increased, this signifies the beginning and not the goal. The university needs to highlight and promote the work we do and reflect the community that we practice in. We need to appreciate diverse perspectives and create an environment and mentorship structure where people can blossom and meet their full potential.

Thank you, Antonio.